Pastors are not ‘professionals.’ Or are we? When you consider that your average congregant now sees a specialist for everything from mental health to diet to career coaching, how do you think they approach the pastoral relationship? Apart from your preaching ministry, you are a spiritual guide, a trusted advisor, counselor, and probably more. The problem is, none of this fits neatly into the kinds of silos we find in the increasingly specialized world of care. Here’s another problem, pastor and elder, you and I spend so much worthwhile time studying to exegete the Bible and mine the depths of historical theology, that we are often under-served in the area of exegeting the human psyche, our subject.

But the biggest problem is this: the single most important indicator (according to psychologists) of long-term health and healing for those in crisis is the nature of social support they receive during and immediately after a traumatic event. Now ask yourself this question. Which kinds of professionals are most often positioned on the front lines to care for those in crisis situations? Yes, we pastors are professionals in this sense, and critical frontline workers.

On February 8, 2018, my firstborn son, Henry, suddenly died in his sleep at the age of 2. He was a beautiful boy. Happy, healthy, and filled with the joy of the Lord. There are plenty of traumatic ways to experience death and loss, but the death of a healthy two year old certainly qualifies. I can trace longitudinally the ways the people cared (or didn’t know how), and how they have affected my healing. I have seen it a hundred times in pastoral ministry. When someone is abused, and they hold the horror within for a long period of time, they struggle to reintegrate, to move back toward wholeness. I’m guessing you have seen it too.

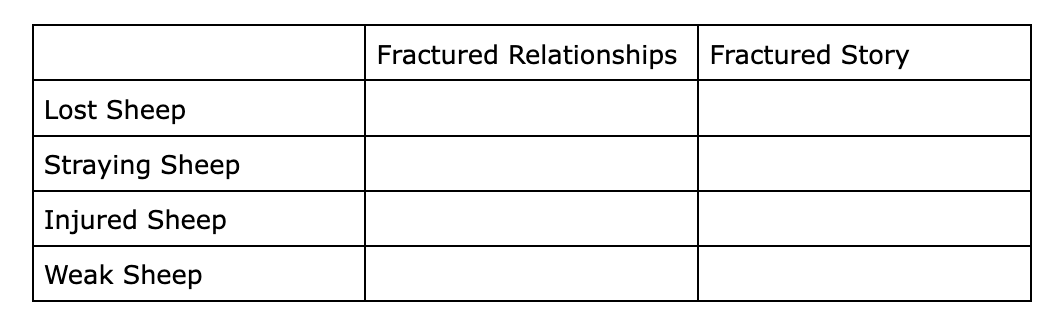

Here is the good news. The Reformed pastoral tradition provides robust resources to deal with these issues. When you map the classical tradition of pastoral care going all the way back to the Patristics, you will discover a very sophisticated methodology. You will also find a single throughline–the metaphor of shepherd and sheep. This throughline comes to its consummate beauty (in my opinion) in Martin Bucer’s 1538 treatise Concerning the True Care of Souls. For Bucer, careful, pastoral assessment of the kind of sheep in crisis was critical. He developed a taxonomy based on Ezekiel 34, in which he outlined the several categories of sheep in Christ’s flock.

“I will seek the lost, and I will bring back the strayed, and I

will bind up the injured, and I will strengthen the weak, and the fat and the strong I will destroy. I will feed them in justice” (Ezekiel 34:16, ESV).

Here, the sheep are all described in a state of distress and need, due to the fallen state of nature since Genesis 3. Each kind of sheep finds itself

in need of healing from the Shepherd. Each will need different interventions. The lost will need to be sought, while the injured will need to be bound up. It is clear, though, that each kind of sheep is in need of particular care from the True Shepherd, and the indictment here against false shepherds does, in no uncertain terms, oblige God’s appointed under-shepherds to tend to these various crises.

As we retrieve this rich resource from the pastoral tradition, we can integrate it with the common grace insight of modern psychology, with the clear and helpful guardrail of Scripture as the final authority–not only for life and godliness, but also for the healing of Christ’s sheep. The model I present happily integrates the best of modern psychology based on that foundation. Here, I lay out a few suppositions, followed by a model I call “Trauma-Conversant Pastoral Care.” It is “conversant” in that the pastor is versed in the language and categories of responsible trauma therapy, but does not pose as an expert. I’ll deal with the limits of the model at the end of this essay.

Supposition: What is Health?

Spiritual and emotional health consist in the biblical ideal of Shalom, which should be understood by its dual aspects of peace and wholeness. Man was made in the image of God, for relationship with God, others, and creation. Shalom, then, is the proper and peaceful ordering of those relationships. Theologian Anthony Hoekema notes of this threefold relationship that

“The proper functioning of the image of God is to be channeled through these three relationships: to God, to the neighbor, and to nature. Man has been endowed by God with the qualities and gifts whereby he is able to function in these relationships. The image of God is to be seen…not just in these capacities…but primarily in the way man functions in these relationships.” (Hoekema, 1986, p. 81-82).

Yet for creatures endued by God with an inner life of knowledge, passion, will, and more, Shalom also entails a sense of wholeness within, which sin has fractured. Counselor Chuck DeGroat points out the cross-disciplinary agreement that one underlying problem for the human person is fragmentation, feeling pulled in many different directions. For example, he cites David Bohm, a theoretical physicist who posits that the psychic and social divisions present in the human psyche must be explained against the backdrop of a foundational need for wholeness that he finds consistent with the Hebrew concept of Shalom (DeGroat, 2016, p. 4). Psychological

fragmentation affects the entire person—mind, body, and spirit. Wholeness, then, involves both physiological intervention and work on one’s inner life, especially including one’s story, the journey from wholeness to fragmentation and back again. DeGroat describes a holistic aim “where neural patterns shift from reactivity to reflection, where the brain functions as a whole, where our invisible bags [our trauma and shame] hold no weight, where head meets heart, where division melts into wholeness” (DeGroat, 2016, p. 121).

Supposition: What is Dysfunction?

From this vision of Shalom, a clear line can be drawn to a biblical-theological and cross-disciplinary understanding of dysfunction. If shalom was the Creator’s design, his ideal for mankind, then the entrance of sin into the cosmos in Genesis 3 has caused shalom to be radically fractured, resulting in relational crisis, inner division, and separation from man’s benevolent Creator. Man has lost the peace and wholeness intended for his flourishing. DeGroat comments: “In shame, we hide behind masks that protect us from ourselves and others. In shame, we live divided lives that rob us of wholeness and peace. Divided and fragmented, we work tirelessly to perfect ourselves but only end up exhausting ourselves” (2016, p. 16). Dysfunction can be summarized as the opposite of peace and wholeness: fractured relationships (with God, man, and nature), and fractured story (or trauma). Since humans were created to exist in relationship with God, man, and nature, any fracture in this threefold relationship will cause dysfunction. This relational strife stems undoubtedly from fractured parts of one’s story, the trauma and shame carried by individuals, events and experiences from one’s family of origin, and more (including, of course, personal sin). If shalom can be summarized under the banners of peace and wholeness, dysfunction entails some level of relational unrest and fragmentation in one’s story.

The Model

The model is simple, and consists of four steps: gentle receptivity, pastoral assessment, referral & partnership, and spiritual counsel & follow up. Gentle receptivity is critical, and is quite simply and powerfully stated in Galatians 6:1: “Brothers, if anyone is caught in any transgression, you who are spiritual should restore him in a spirit of gentleness.”

Pastoral assessment maps the classical categories of sheep in Bucer’s taxonomy against the health categories of relationships and story. The pastor may want to make notes based on a grid which maps a congregant’s struggles thus:

In cases of domestic abuse, as one example, we are probably dealing with an ‘injured’ sheep who, though she may be stuck in a presenting sin of her own, is primarily traumatized by the sins committed against her. Her ordinary relationships are fractured (marriage & family), and her story most certainly has fractures (though the pastor himself will need to be curious enough to learn about her story).

The reason such an assessment is critical is that you will want to treat this person quite differently than someone who may be a ‘straying’ sheep, caught up in high-handed rebellion against God and man. I have heard of sessions who were so quick to deal with the “presenting” sin of an abuse victim, that they completely missed the trauma she has experienced and therefore set her healing back by years. Yes, this is extreme, but it illustrates the point that proper assessment matters.

You will also want to recognize the limits of pastoral care, and move to step three, referral & partnership. In many cases, the dysfunction is far too complex for pastoral counseling alone. A pastoral counselor should have the humility and knowledge to understand the need for quick and careful referral. If possible, the pastor should obtain permission to partner with the therapist and help pray for and work toward the spiritual healing that is necessary alongside of (or well after in severe cases of trauma) trauma therapy.

Finally, spiritual counsel and follow up will be needed. In the case we’ve been exploring, a care team will need to be established. The pastor must recognize his limits, and must recognize the need for the body to minister to this dear sheep. The pastor (along with others) will be called upon to pray with and for the sheep, to listen, to continue a partnership with a therapist, and more. The pastoral counselor’s goal is spiritual healing, in connection with other professionals to bring about a holistic movement toward true shalom. While the pastor is limited to his own area of expertise, the model outlined above should demonstrate that wholeness in relationship and story are the chief ends of the process.

Limits and Conclusion

The benefits of this model for pastors are found in its limits. A pastoral counselor cannot and should not attempt to heal every crisis-related problem of a parishioner. Further, in a small to medium church context such as the one I inhabit, the limits of this model protect the pastor from burnout while also providing proper pathways for real engagement in pastoral counseling, a key piece of any pastoral ministry. The model itself, with its progression from pastoral assessment, to referral, to follow up ensures that the pastor is both intimately involved but also not solely responsible for the healing of wounded, hurting, or straying sheep. It also allows room for the pastor to turn to crisis care teams, loosely overseen by the pastor, who have more regular “hands- on” interaction with the parishioner, thereby freeing the small church pastor for the other demands of congregational life.

Trauma-Conversant Pastoral Care serves as a “middleware” between ordinary pastoral situations and clinical or trauma-informed therapy. It is my deep conviction that this middleware is greatly needed. It serves as a helpful guardrail for pastors who seek to fix every problem, but it also provides an ongoing support and accountability structure that is often lacking in traditional therapeutic relationships. The pastor is able to follow up, to continue in spiritual counsel, and especially to help in long-term relational healing in ways that are less practical in clinical settings. Most importantly, the church and its leaders are able to tangibly, manageably follow the charge in Scripture to care for the sheep in Christ’s flock through this historically rooted system of diagnosis and its corresponding remedies. May the Good Shepherd use this critical ministry for the care and growth of every sheep in his flock.

Alex Dean (M.Div, MACC) is lead pastor of New St. Peter’s PCA in Dallas, TX, where he lives with his beautiful wife and three spunky daughters.